Why I Love Unreliable Narrators

We all like to believe we are aware of who we are and what is real. We want to believe that we are good people and that our story is true. But what if you were just completely insane or immoral? What if you might be less than an ideal person? Or a serial liar? These sorts of questions are such that we prefer to not ask ourselves, let alone consider them. Well, those sorts of questions fascinated me as a writer and as a person. Let’s chat about my favorite uses of the Unreliable Narrators in the literature using some of the best in the field!

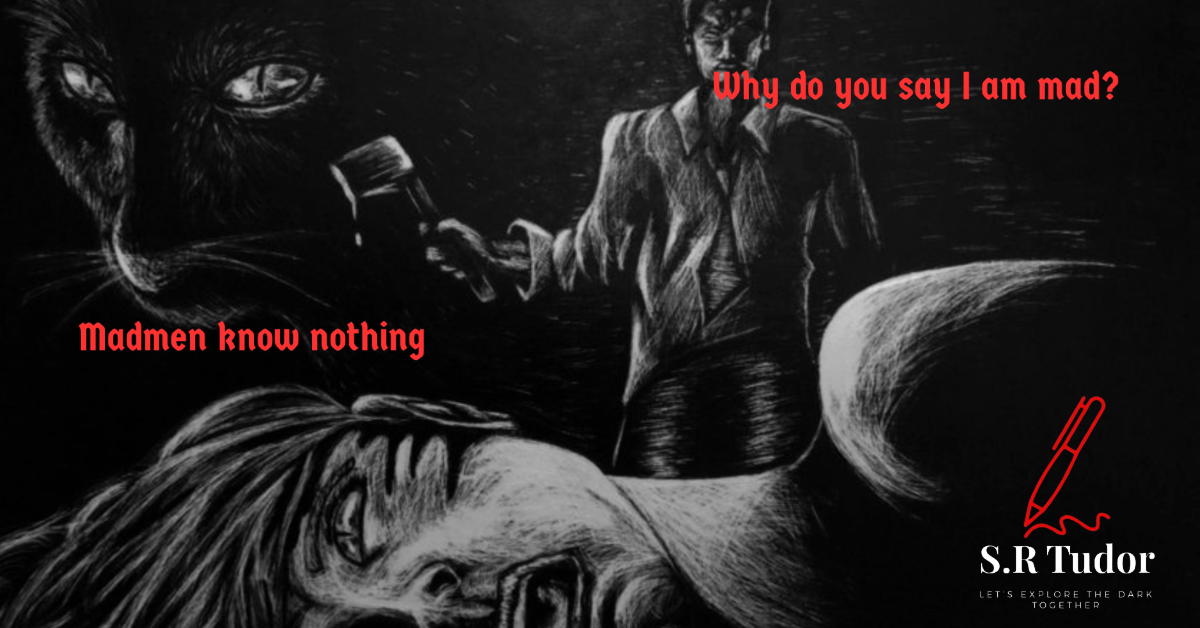

Poe:

True! — nervous — very, very dreadfully nervous I had been and am; but why will you say that I am mad?

The Tell-Tale Heart by Edgar Allen Poe

Poe’s protagonists are often unreliable if not outright delusional. Some of his most famous short stories like The Black Cat, The Tell-Tale Heart, and The Cask of Amontillado all include first-person narrations by people who are hella sus. The Tell Tale Heart, for example, is entirely told from the perspective of a madman trying to convince you: the reader that he is not mad. The horror comes from the dissonance the reader experiences as they watch the man casually explain why he would kill his roommate because of a bad eye.

The lack of self-awareness by the protagonist is often a source of horror, and intrigue for the reader. It (to paraphrase from Ted Ed) turns them into active participants, trying to figure out what happened during the story. The Cask of Amontillado is also an example of this, albeit in a more comedic context. The nameless protagonist claims he wants to kill the ironically named Fortunato because of an insult. The protagonist doesn’t provide us with an example of this insult, but we are assured that it is bad enough to kill a person

It was probably a really poor your mama joke.

So, is the protagonist justified in killing Fortunato? Honestly, I don’t think so, but that is where the participation comes in. You, the reader, have to pay attention, consume the text carefully, and come to your conclusion. Was the protagonist insane?

Or was there some real hostility between the two men that justifies the murder in the eyes of the protagonist? The Black Cat contains a more sympathetic main character, in that story, Poe condemns the horrors of alcoholism by showing how destructive it can be.

The protagonist in drunken rages torments an innocent cat, Pluto, eventually killing it, and is haunted by the guilt of the deep as a result. The story culminates with the protagonist killing his wife and hiding her in the walls. Only to discover the cat they adopted earlier to have been accidentally buried with his wife, betraying his crime.

The Black Cat is one of Poe’s best for good reason. Aside from the horrors of a man abusing his beloved pet in drunken rages, he is also textbook unreliable. After Pluto is hanged, the house burns down for some reason, except for a wall with the soot shadow of a hanged cat, implying that the cat caused the fire when there is no reason for us to believe him.

After the second cat is adopted (a splitting image of Pluto) the white spot on the cat’s chest starts to change into a hangman’s rope. Poe writes a truly harrowing story about guilt and self-destruction with a POV character spiraling into madness brought on by his foolish actions.

The perspective tells us a distorted version of what might have happened, we follow the twisted logic of all three protagonists in this section. They are puzzles within the text that deliver chilling reasons for their actions. This is why I love unreliable narrators in Poe’s stories, they are extremely human but often supremely demented. They add another dimension to the story that wouldn’t have been there otherwise. Poe knows how we are all capable of our self-destruction, and in the case of Cask, how we can commit evil. Our stories can sometimes be only real to us. Speaking of which

Nabokov:

What I have noticed when I observe interviews with truly monstrous people, typically child/ animal rapists, murderers, and abusers, is how they rationalise their evil deeds.

They either deny it, romanticise it, or justify it and sometimes they will downplay it. However, any of these show a distortion of perspective against an absolution of reality.

Vladimir Nabokov is very interested in the horrors of humans and loves to explore how terrible people frame themselves and their actions. The most famous example of this would be Lolita, not just a textbook case of unreliable narration but also offers an in-depth exploration into the mind of a monster.

Humbert Humbert is a monster who is desperately trying to prove to you, dear reader, that is not a monster. All the while inadvertently proving how monstrous he is. The preface from the fictional professor John Ray Jr describes Humbert Humbert as “morally leprous”, a very clear indicator on how we shouldn’t trust the author. John Ray is the only reliable narrator, or the closest approaching a POV with a moral compass.

The rest of the novel is told from Humbert Humbert’s very twisted moral code. A great example is way he describes his amusement in manipulating people and making people see him in a way that suits him best.

“I discovered there was an endless source of robust enjoyment in trifling with psychiatrists: cunningly leading them on; never letting them see that you know all the tricks of the trade; inventing for them elaborate dreams, pure classics in style (which make them the dream-extortionists, dream and wake up shrieking); teasing them with fake ‘primal scenes’; and never allowing them the slightest glimpse of one’s real sexual predicament.”

Lolita part 1 chapter 9

We see how Humbert Humbert attempts to twist and manipulate the reader with how he frames events, such as when Charlette mysteriously dies in a car accident following her discovery of Humbert’s lust for her daughter. He claims a car hit her and drove off, conveniently just as she was trying to warn people of his disgusting tastes. We only have his word for it, given how he likes to trick people and foster elaborate situations where he is not to blame.

It’s not too difficult to be suspicious of him, given his motivation and how he kidnaps Lolita and becomes her sole protector. My favourite moment is when Humbert Humbert, after drugging and assaulting Lolitia in a hotel bedroom, springs out for lunch telling himself that he didn’t assault her. Lolitia’s Humbert Humbert is a brilliant examination of a broken individual who is constantly trying to seem like the tragic hero in a romance.

He can’t be a rapist and child predator because that would mean he is a monster. One can never admit to being a monster. This reflects the reality of predators, there is always a reason why they are the victims of society. Nabokov understands this and forces the reader into the head of such a predator, exposing just how delusional they can be. He also shows us how dangerous predators are to society at large.

Flynn:

Most stories with unreliable narration are told from a single point of view, not surprising really as it is hard enough to keep one story straight let alone two. Gone Girl however, is not such a book.

Gillian Flynn crafts a masterful thriller that jumps between Amy and Nick Dunne, both of whom are claiming to be the victims of each other until we discover everyone is a bad person. Amy Dunne is a terrifying force of nature, weaponizing the press and public perception against her admittedly cheating husband.

We witness just how thin our outward persona can be and the darkness hidden under the picturesque ideal of the perfect family. As much as we want to present ourselves as a normal pleasant group, we are all just a few actions away from becoming a monster.

Gillian Flynn uses unreliable narration to highlight the hypocrisies in ourselves, we all want to be the hero, and we all want to be seen as the protagonist regardless of our actions. We craft and nurture our perfect persona to appeal to society. A facade that will get crushed should anyone fail to take it at face value. Flynn’s take on unreliable narrators is very similar to that of Nabokov’s, both examine the mundanities of evil through people who might not want to be seen as bad.

But unlike Nabovkov, Flynn examines the different levels people become unreliable narrators, Nick is a bad person, he cheated on his wife. But he didn’t deserve to get framed for murder, socially ostracised, and his family torn apart by Amy. Amy is more monstrous than Nick. but both are in different capacities bad people. Flynn examines a different kind of social ill, the pervasive inauthenticity of society, and how killers can hide behind it.

Lovecraft:

One thing about Lovecraftian protagonists and the general POVs is that they are normally honest about the horrors they are talking about.

If they are unreliable, they are unreliable because of the absurdity of the nightmares displayed in the text. We don’t quite know if the events of The Colour Out of Space or At the Mountains of Madness are real or just the perspective of a madman struggling to deal with tragedy.

We don’t have any reason to believe that they might be lying or deluded like Poe or Nabokov nor do we find out they are malicious like with Flynn. Lovecraft’s protagonists are judged as unreliable narrators because of their experience, or the narrative has been recorded by a third party, interpreted through the lens of one or multiple independent storytellers.

The Colour Out of Space is told from multiple perspectives, firstly from a journalist who is investigating a dying town, discovering another old man who then relays the information of the event that occurred at some time in the past to us. We are processing the information that is The Colour Out of Space from at least two sources.

Sources that seemingly are getting their information from memories, an inherently unreliable place. The Colour can be framed as a story about a myth, something horrifying that causes the death of communities, something to explain decay.

At the Mountains of Madness is also very similarly framed as the lone survivor of a tragic Arctic expedition retelling the events to try and explain what happened. We only have his perspective on the issue. Whether we want to believe a traumatised man trying to make sense of the horror he witnessed, is entirely up to us. You will notice that Lovecraft’s narratives are normally ones recalled after the fact. Much like The Colour Out of Space, The Call of Cthulhu, Dagon, and The Shadow over Innsmouth are recorded and delivered to the reader after it has already happened.

Lovecraft’s protagonists are unreliable by the virtue that they are reliant on their memories. They are also often driven mad by the revelatory glimpses of the cosmos, adding another layer of unreliability to the horror. Lovecraft’s POVs are an example of myth-making, oral history passed down, twisting things slightly each time with each retelling.

Lovecraft’s use of unreliable narrators is less about exploring the failures of being human and rather how we as humans try to deal with history and life. How we try and rationalise cruelty and horrors in our time. Lovecraft worked with unreliable narration to explore how we as humans rationalise our insignificant existence, an exercise in myth-making similar to Slenderman today. The Cthulhu mythos is a constellation made up of unreliable narration, twisted into strange and terrifying implications, all pointing to our insignificance in the universe. Lovecraft weaponizes unreliable narration into humbling humanity.

Conclusion:

Unreliable readers, when done right, are enjoyable to the reader. They, to quote again Ted Ed, turn their readers into active participants. The reader needs to figure out who is telling the truth and what might have happened. The unreliable narrator offers another level of engagement and depth to the characters that might not have been there otherwise. The plot becomes a puzzle to test the reader’s media comprehension skills, and I am all for that in literature!